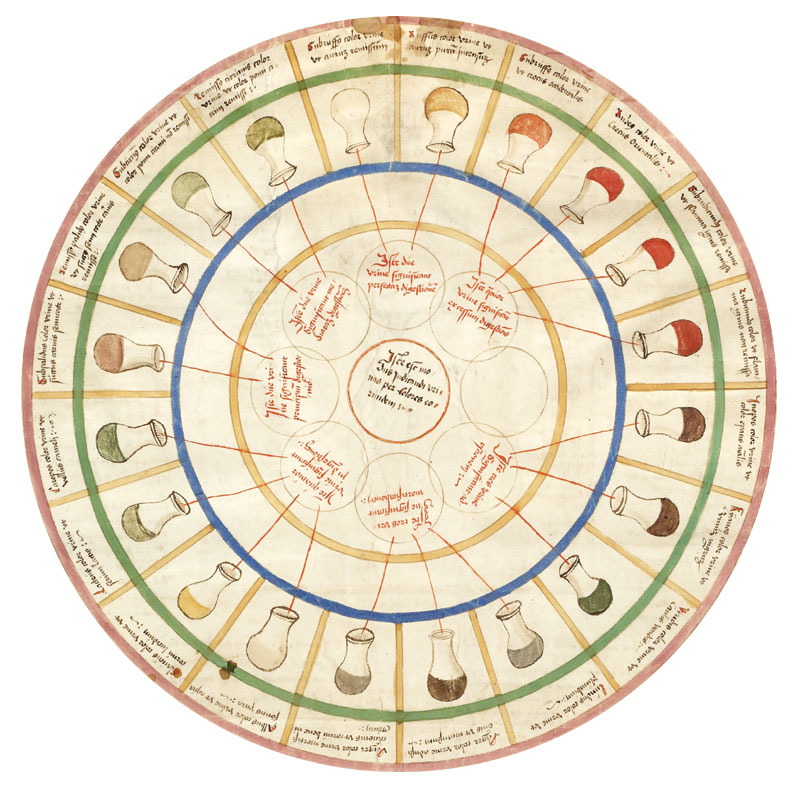

Ulrich Pinder’s urine wheel is a thing of beauty. Created in 1506, it describes the colors, tastes and smells of urine belonging to people in various diseased states. Image from this Nature article on “metabonomics,” the modern-day equivalent.

Scholarly Attitude

I shouldn’t enjoy it as much as I do, but I love when I can spot a scholar’s dislike of a historical personage—it shows their humanity. Perhaps the pretense of neutrality is what makes us academics so vitriolic when writing in nonacademic settings. FINALLY WE CAN LASH OUT.

Here’s what Susan Karant-Nunn has to say about Calvin:

“Calvin’s expatiation on Christ’s suffering is almost nil. Having, we assume, read the scriptural text aloud, he then refers to it almost obliquely, as a springboard for his remarks on Christians’ moral condition, which is poor.”

It’s veiled, but it’s there–the not-quite-scholarly use of “nil,” the sarcastic rhythm, the clipped end of the second sentence.

“The emotional trajectory of these Passion sermons is then upward; the congregation is taken from the horror and depths of its corruption to, in conclusion, the possibility of reconciliation with the Heavenly Father. Perhaps the series should have ended on this note.”

So delightfully dry! Why, you ask, should it have ended on this note?

“But in the final sermon, on the Resurrection, Calvin remarks on the fact that the women who went to Christ’s tomb preceded the disciples in hearing the astonishing news. In telling about the Resurrection first to women, who are by nature weak, ignorant, and infirm, God wanted to demonstrate ‘the humbleness of our faith.’ The men, normally elevated and designated to engage in public transactions, deserved punishment, in any case, for having abandoned their master. But God accepts the service even of the weak–he is referring here to the women.”

How about this?

“Unquestionably, Calvin adheres to the doctrine of the atonement; it is central to his conception of salvation for worthless humankind. Yet, so important is it to him to impress his charges with their worthlessness that he resorts to the emotive vocabulary of shaming and condemnation. His language is extreme, and it is designed to break down any lingering sense of self-worth and self-reliance in those around him. His initial stress is upon the nullity of human self-esteem. He proffers the atonement only secondarily, after he has rhetorically (he hopes) reduced his audience to the verminous level to which he repeatedly assigns it.”

Whew. (Also, incredibly effective as a piece of persuasion; I had no particular feelings about Calvin before, but I like Calvin him a lot less after reading this.)

In Which John Rewrites Matthew and Jesus is Nice Again

I wrote a facetious post on Matthew 26:6-11, an episode in which a woman pours ointment on Jesus’ head and the disciples complain on the grounds that ointment is expensive and the proceeds from its sale should have been used to help the poor. Christ replies (in what I characterized as an asshole move) that she was right to do as she did, since the poor will always exist, but he won’t be around forever. Being in an irreverent and unscholarly mood, I left out the last line of Christ’s response: “For in that she powred this ointment on my bodie, she did it to burye me.”

It never pays to mock the Bible before you’ve done your research. I’ve since read further in my facsimile 1560 Geneva Bible. If you know your Gospels, you know that an almost identical episode takes place at John 12:3-9. Jesus is at Lazarus’ house when Mary, instead of pouring the ointment on his head, uses it to wash his feet:

Then took Marie a pound of ointment of spikenarde verie costlie, and anointed Iesus fete, & wipte his fete with her heere, & the house was filled with the savour of the ointment.

Then said one of his disciples, euen Iudas Iscariot Simons sonne, which shulde betraye him,

Why was not this ointment solde for thre hundredth pence, and giuen to the poore?

Now he said this, not that he cared for the poore, but because he was a thefe, and had the bagge, and bare that which was guen.

Then said Iesus, Let her alone: against the day of my burying she kept it.

For the poore alwayes ye haue with you, but me ye shal not haue alwaies.

Before diving into this, here’s a caveat: I’m obviously not a Bible scholar, but I was, once upon a time, a pretty fervent Bible reader. When I was eleven or twelve and really religious, I decided to read the Bible all the way through. I had a Precious Moments Bible and a plastic hologram bookmark and set to, plowing through Genesis and Leviticus and Numbers and the horrors of Judges, by which time my eyes were bulging out of their sockets at all the concubine butchery and rampant murder, adultery, and polygamy. By the time I got to the end of the Old Testament I’d overdosed on swallowed questions and doubts and given up the project. Never got to the New Testament. Point being, I read the Bible with a suspicious eye, but the suspicion is less objective and scholarly (I mean, why bother?) than it is readerly: in the way readers want closure from a story, I want the New Testament to redeem what the Old Testament made terrible.

From that viewpoint, Jesus’ insistence that the disciples won’t have him always, even though they’ll always have the poor, is so irritating. It smacks of self-love and it contradicts a basic tenet of Christianity: they will have Jesus with them always. That is the whole point. Jesus’s claims to transcendence and divinity don’t get switched off just because he’s talking about his carnal body*. On the other hand, the disciples won’t have the poor with them always: poor people die every day. Only if you regard the poor as an unindividuated mass can such a statement make sense. Is that really how Jesus sees the poor? As a demographic?

Seen as storytelling, it’s interesting that this version of the episode in John (with a slightly different cast of characters) makes the episode in Matthew much more palatable, despite almost identical dialogue. First off, the fact that JUDAS objects to Mary’s anointing of Jesus’ feet gives us a clear sign that this instinct is wrong. This isn’t the case in Matthew, where several disciples raise the point and seem to genuinely want to help the poor. John implies that the poor wouldn’t get the money anyway since Judas is a thief. In that case, obviously Jesus should receive the benefit instead of Judas. The interesting moral dilemma raised in Matthew is attenuated here, thanks to the appearance of Judas the Bad Apostle. Prolepsis wins.

Speaking of prolepsis, the proleptic angle I left out (“she did it to burye me”), which comes at the end of Matthew, appears before the dismissal of the poor in John. This drives home a point that sinks into near-irrelevance in Matthew: Jesus is going to die, and true believers sense this and are subconsciously preparing him for burial. His insistence on his right to anointment is thereby transmuted from a pretty unconvincing defense of luxury (in his special case) into an acceptance of death. He’s accepting a burial rite before he’s dead. The line about the poor has much less force this time round.

In the language of creative writing workshops: Good rewrite, John!**

*I concede that the point of the Passion is to shock believers into experiencing the loss of Jesus’ body—without focusing on his body there can be no guilt at his sacrifice, and no redemption. That doesn’t change the peculiarity of Jesus insisting on how much people will miss him.

**Totally spurious claim; I have no idea which gospel was written first.

Ointment For Asshole Jesus

If I stopped to mark all the Biblical moments that give me pause, my Bible would double its weight in sticky notes. (Sticky notes are the mattress-mites of academic books.) However, I just got the shiny new facsimile copy of the 1560 Geneva Bible, which means I get to experience verses I’ve already read again, this time with the benefit of 16th century marginalia and its alienating typeface, both of which somehow make it easier to be an ahistorical twat. One of the privileges of the early modernist is that—on your least mature days—your work is interrupted by episodes of rolling around in weird English like a psoriatic pig in mud. Shakespeare notwithstanding, there are days when sixteenth-century English sounds like David Sedaris’s French in “Me Talk Pretty One Day.”

This is one of those days. On another day like it I’ll get down to business and actually make my Bible verses comic series, but in the meantime, draw your own mental picture from this little episode:

“And when Iesus was in Bethania, in the house of Simon the leper, There came to him a womá, which had a boxe of verie costelie ointemet, & powred it on his head, as he sate at the table.”

That’s Matthew 26:6-7.

For those of us willing to cast historical contingencies aside, there are already MAJOR ISSUES. Some random gal just gallops on in and pours a box of super-expensive ointment on Jesus’ head?

The first question to strike the discerning reader is how do you pour ointment?

The second is likely to be how did Jesus feel about a box of ointment (again–a BOX of OINTMENT–who knew it came in boxes? I just can’t imagine an unlikelier phrase, and imagine what getting it off would take in a pre-detergent age) being poured ONTO his head?

Did it get into his eyes?

His disciples were annoyed, though not, as you might expect, because they hated to see their leader BLINDED by OINTMENT in a career-ending mishap*:

“And when his disciples saw it, they had indignation, saying, ‘What needed this waste? For this ointment might have been sold for much, and been given to the poor.”

Now, were I to have an indignation at a woman who waltzed in an doused my friend in ointment, this is not the first indignation I would have. But I respect it: evidently the box of ointment was very costly, and the whole incident does seem very wasteful. Fair if slightly tangential point, disciples.

To which Jesus replies, “Why trouble ye the woman? For she hath wrought a good work upon me. For ye have the poor always with you, but me shall ye not have always.”

At this, even the Christianest of Christian readers’ eyes goggle. Screw the poor, they’ll always be around! Jesus says, like someone on the set of Entourage instead of, oh, Hope Incarnate For All Mankind. Crazy lady here had the sense to spoil me. TAKE NOTES, FELLAS.

But this is where the ahistorical twat within me reconciles, after an airport chase, with history. Because the marginalia in my shiny new 1560 Geneva Bible shows that sixteenth-century readers were going out of their minds at the cognitive dissonance here too. “This fact was extraordinary, neither was it left as an example to be followed,” they say, in what might be the most diplomatic way you can (as a Christian) say DON’T LISTEN TO CHRIST HERE HE’S VERY TIRED, AND ANYWAY, HE DOESN’T HAVE A HEAD FOR US TO DOUSE IN OINTMENT ANYMORE, SO: “Also Christ is not present with us bodily or to be honoured with any outward pomp.”

And that’s why I love what I do.

*I’m modernizing spelling for the rest of this

How To Kill the 17th Century Serpent in Your Garden of Eden

John Dunton, one of my favorite late seventeenth-century fellas (of whose Athenian Mercury I wrote a series for The Awl), decided to amalgamate “extracts and abridgements of the most valuable books printed in England” between 1665 and 1692. It’s called The Young Students’ Library, and there’s an entry on what I’m 90% sure are modern-day rattlesnakes. Here’s the description:

“There are in several Places of America a kind of Serpents, most dangerous, which is called the Bell-Snake, because with the End of their Tail they make a Noise very like that which Bells do, when they are moved. This Animal is very big, about five Feet long, and of Brown Colour· mixed with Yellow: It hath a forked Tongue, and long sharp Teeth, and moves with as much Swiftness, that it seems to Fly.”

Worrisome. Dunton helpfully includes the ways and means of killing it. According to a Captain Silas Taylor, what you do is poke it with a stick, on one end of which you’ve put some “wild Pouliot” leaves, which are rattlesnake-kryptonite. Here’s Taylor in his own words:

The wild Pouliot, or the Dictam of Virginia, is about a Foot high, the Leaves are like unto those of the Pouliot, and little blue Knots, at the Places where the Branches are joyned to the Trunk; and though the Leaves are of a Red Colour, inclining to Green, the Water, which is distilled thence, is of a fine Yellow, and is like Brandy. When these Leaves are opened and put upon the Tongue, they seem very hot and pricking. They take of these Leaves, which they tie to the End of a splitted Stick, and some one puts it very near the Nose of the Bell-Serpent, which useth all its Endeavours to draw away from it, but the Smell, as it is believed, kills it in less than half an Hour.

America might a new Garden of Eden where a New Jerusalem could be built, but it comes with the serpent. Of course, it also comes with a handy serpent-killer. The OED tells me dictam is a labiate plant that was thought to be medicinal. Not just medicinal—magic. Cretan dittany was said to be able to expel weapons. Its American cousin was also known as pepper-wort and (fittingly enough) Snake-Root.

But how well did work?

“This Experiment was made in Iuly 1651. at which Time it is thought the Venom of these Animals is in its greatest Strength. This Gentleman also assured the Royal Society, That where ever the wild Pouliot groweth, or the Dictam of Virginia, there are no Bell-Serpents to be seen.”

In short, to keep your Eden serpent-free, be a good gardener. Plant wild Pouliot and keep the devil-bell out.

“I Am All Over Phlegm”–A Bad Letter-Writer’s Apology

I’m in the middle of transcribing some 4000 images I took of the Lister MSS. at the Bodleian—a collection of letters and other documents written to and collected by Martin Lister, 17th century physician and eventual member of the Royal Society.

One under-explored aspect of this particular archive (which includes luminaries writing about the circulation of plants and other Matters of Import as well as patients writing to Lister for help) is the way in which the malfunctioning body allows letter-writers to finesse social gaffes. As someone continually apologizing to friends for falling out of touch because of migraines, I admire how Richard Bulkeley apologizes to Lister for not writing sooner:

“My long silence since the receipt of your last (for which I heartily thank you) has not proceeded from my want of affection or respect nor even from forgetfulness, but from that Languor of spirit that I now lie under, a listlessness, a lentor of mind, for indeed it is a month since I first took in hand to write to you, & have sat to it at least half a score times since. But as the Vulgar speak (& they little know how truly) I am all over phlegm, this Viscous pituita so visible to me both in Excrement urine & its other effects, does likewise so habitate my Brain that I am good for nothing.”*

*Spelling has been modernized.

Two Heaths

Last night there was a storm. A true storm. A strong storm, the kind where the lightning illuminates your kitchen along with the whipping sheets of rain.

We don’t get those much in California, and my Twitterfeed exploded with reactions. Several people said they heard applause coming from other apartments. Some got caught in the rain. Violent weather makes you grateful for the shelter that divides you from the sublime. It also forces you to try—and fail—to imagine the direct encounter.

So you think of King Lear. And of other people—fugitives, say—who once overused their power, trusting their unearned immunity from reprisals.

[slideshow]

I’d forgotten that Lear’s famous storm scene happened on a heath. Prior to this recent trip to England, all I imagined when I heard the word Heath was Wuthering Heights and the moors from The Secret Garden. Heaths and cliffs were the wilds of nature where passion ran rampant.

Two weeks ago, I finally saw a heath—Hampstead Heath. I saw it on a golden afternoon, away from my own country’s ravages and bizarre storms, during a week when even England was mystified by its unprecedented sunny warmth.

It was the essence of pastoral, all gentle greens and gorgeous rolling hills.

The walk to the Heath started off symbolically. Our host had suggested we walk from her place in Hornsey along a railroad track that had been turned into a wooded path until we got back into town, and then suddenly, there the heath would be.

We didn’t completely understand the instructions, but we set off anyway. We found the railroad track, where even the trees performed the harmony between nature and industry:

When the woods ended, we arrived, as promised, at another part of London. Here, too, the walk was unaccountably accommodating. Here, the streets on the way to the Heath said, take a rest. Have a seat!

The streets and houses arrayed themselves in attractive rows:

And then things got green.

Two people sat under a tree.

Two trees sat next to a lake.

Afternoon melted into evening, and all the tiny people on the heath lined up on the horizon and became silhouettes. One was a dog. One flew a kite.

It’s as hard to imagine this as the site of Lear’s confrontation with the elements as it is to imagine being out on a night when you’re in. I was conscious, on this walk to a heath that violated all my notions of heath-hood, that my image of England—which had been grey when it wasn’t wild—was now pathologically skewed toward an impossible ideal. I didn’t live there. I hadn’t met the bad parts. All I saw was that the streets of London proffered velvet chairs. And the heath spread out in a bucolic fever dream of reflective waters and bridges and idyllic benches.

It’s the lunatic perfection of Hampstead Heath that convinces me, if only in the abstract, that Lear’s heath is there too. And there, like here, where the thunder shatters the windows in a fit of strange weather, the going—for those outside the magical brackets of windows and trips—shall be used with feet.

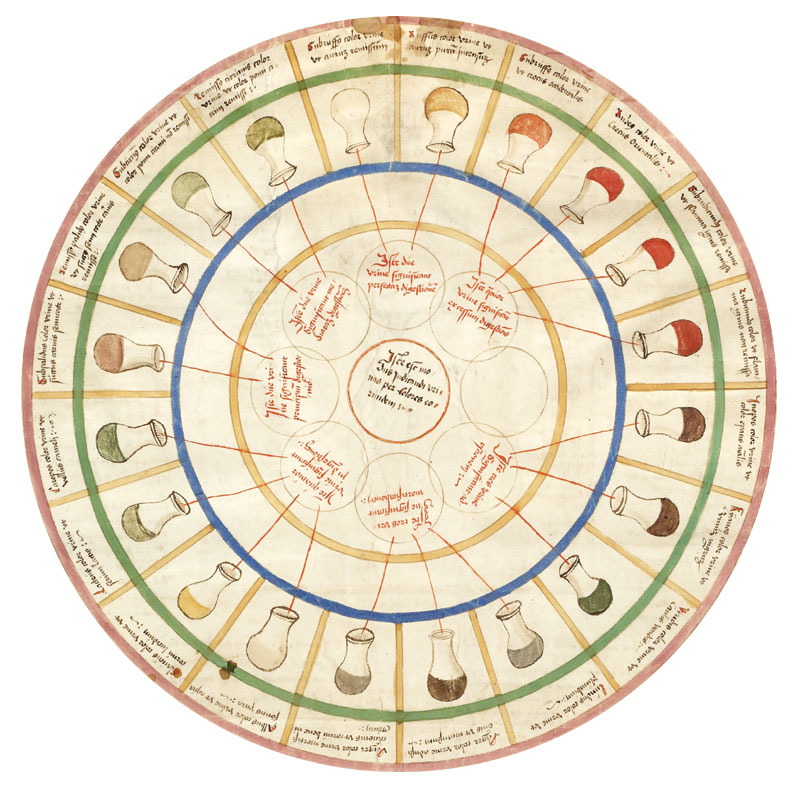

If it Craps Like A Duck: The Thrills of 1742 Automata

This 1742 handbill for an exhibit of automata describes three mechanical devices imitating life. The first represents a man playing a German flute, the second, a man playing the pipe and tabor. As for the third:

Another news cutting, issued on the day in question, clarifies—by the sheer number of lines devoted to each subject—what sensation-seekers were demanding most:

The German Flute gets a passing mention, as do the tabor and pipe, but the star of the show will be a robotic duck, doing its best to convincingly eat, groom, and shit onstage.

A Cure for Balding

Joannes de Mediolanus’ 1528 cookbook is full of intriguing accounts of what food does to bodies and bodies do to food. Here, he prescribes onions as

- an aphrodisiac

- an antidote for dog bites

- a tremendous cure for baldness

- and warts

- the opposite of a cognitive enhancer

(Spelling has been modernized.)

Onions sodden and stamped restore hairs again, if the place where the hairs were be rubbed therewith. This is of truth when the hair goeth away through stopping of the pores and corruption of the matter under the skin. For the onions open the pores and resolve the ill matter under the skin and draw good matter to the same place. And therefore, as Avicen saith, oft robbing with onions is very wholesome for bald men.

Wherefore the text concludeth that this rubbing with onions prepareth the beauty of the head: for hairs are the beauty of the head.

For a farther knowledge of onions’ operation, witteth that they steer to carnal lust, provoke the appetite, bring color in the face. Mingled with honey they destroy warts, they engender thirst, they hurt the understanding (for they engender an ill gross humour), they increase spittle, and the juice of them is good for watering eyes and doth clarify the sight, as Avicen saith.

Farther note that onions, honey and vinegar stamped together is good for biting of a mad dog.