Fresh off the plane from England, I went to the grocery store for the express purpose of buying conditioner.

I had left my half-empty bottle in Stratford-upon-Avon because I’d filled my suitcase to bursting and had two separate nightmares about hauling it up and down the Tube’s liftless stairways. (That the Tube had no lifts was not part of the nightmare; it was just, to borrow a phrase from the Royal Society, whose correspondence I’d been reading, a “matter of fact”.)

My friend and host Will walked in just as I was zipping up the last piece of luggage to ask whether the bottle he’d found in the bathroom was mine. I made a virtue of oblivion and said why yes, it was, but I’d decided, very sensibly, to leave it. “They have conditioner in the States,” I said, in that obnoxious way people do when they’re new to England and pretend that “the States” is how they regularly refer to home.

This was the bottle in question:

My fellow-traveller Irene had abandoned me the day before, just as I was now abandoning the bottle of conditioner. Of the two of us, the conditioner was better equipped to navigate the streets and undergrounds and overgrounds of London. As long as Irene had been with me, I would nod emphatically as she pointed out a route to me on the London A to Z. I hadn’t the heart to tell her that the series of looping pink and yellow lines punctuated by Underground logos was experientially identical to staring at a Jackson Pollock painting. If she really wanted me to understand, I would have to spend at least 45 minutes staring at the map trying to figure out how the damn thing worked. Some people learn to read maps as children and find that the skill transfers to other maps. For me, there’s no crossover between a world map and a road map. Every map is an completely alien syntax that I have to learn from scratch.

Having pulled up the tfl map, I refused Will’s kind invitation to go to the Shakespeare Institute’s library in order to stare for two hours at my computer screen, which showed me this:

What I see when I look at this is a bewildering intersection of colored lines with alternating grey and white patches whose thicknesses vary according to no discernible principle. Those areas marked with numbers–5,4,3–had something to do, I knew, with these “Zones” Irene kept talking about, but I had no grasp of what those zones referred to, or why they existed, or how many I needed to cross. They were the stuff of science fiction—a weird series of concentric amoeba or Russian dolls that we were somehow supposed to instinctively understand.

If the London A to Z was a Jackson Pollock Choose Your Adventure, the Tube Map reminded me of those movies where Harrison Ford has to stop a bomb from detonating, except that if someone said “cut the blue one” to him, there were at least four different wires they could mean. “Cerulean or sky-blue?” he’d snap. “Navy-teal,” Anne Heche would reply, sexually.

By the time Will got back, my screen was badly smudged from my efforts to follow the Piccadilly and Northern lines with my fingers.

But I managed, and determined that there were two different ways to get to the airport the following day. By “determined,” I mean that—unconvinced I’d gotten anything right—I ended up consulting Will and Google Maps for directions.

There seemed to be two routes that would work, once I managed to get myself out of Stratford-upon-Avon and to London. (This is as far as you get when you’re built like me—there seem to be two routes, true, but ultimately it’s a leap of faith.) One was taking the Tube, the other was taking the train.

Knowing I would forget them the minute I needed them, I wrote them down on some old train tickets.

I labeled the first leg of my journey A. Here is what the front of the ticket containing route A looked like, just so you can get a feel for the thing:

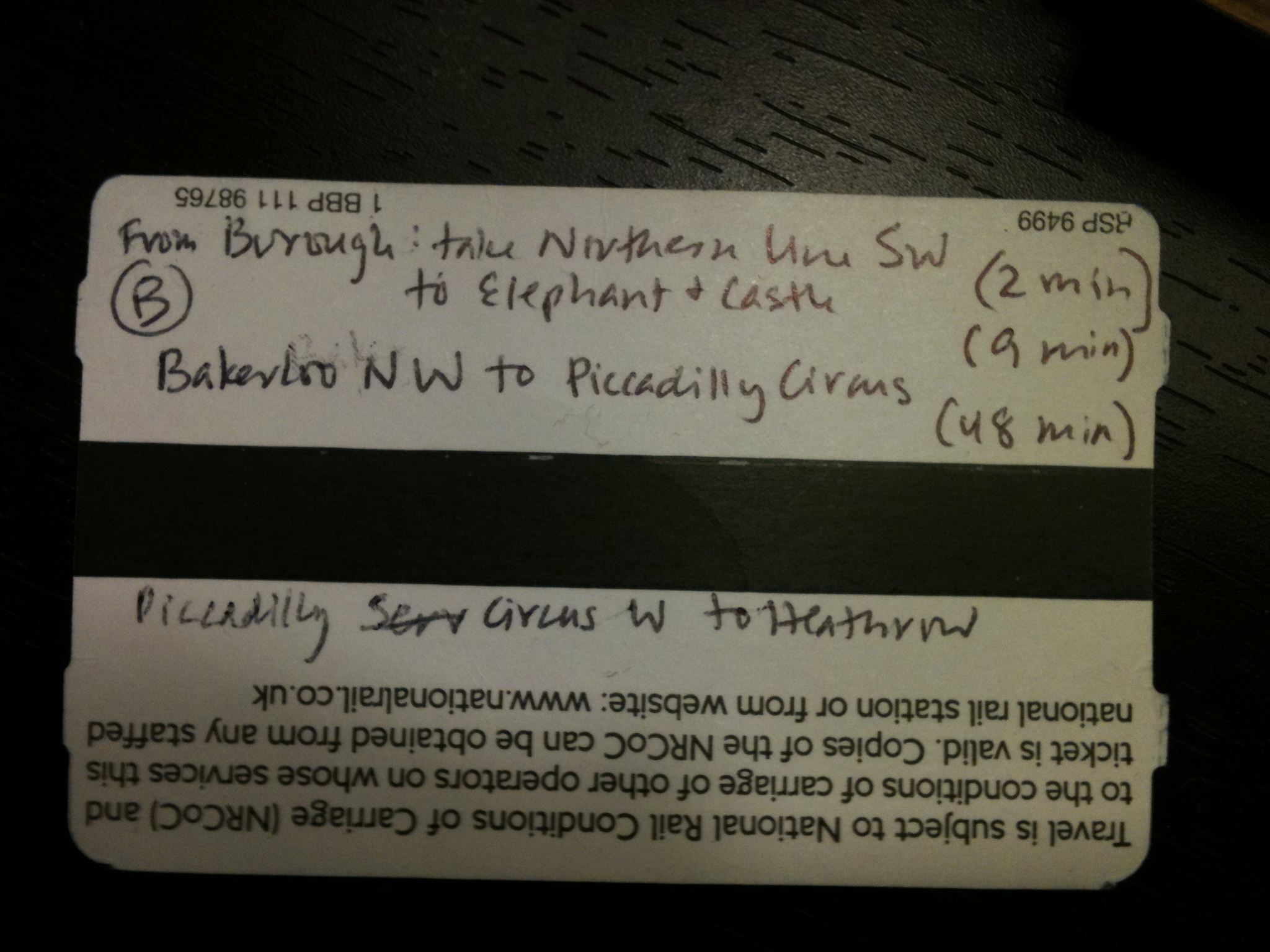

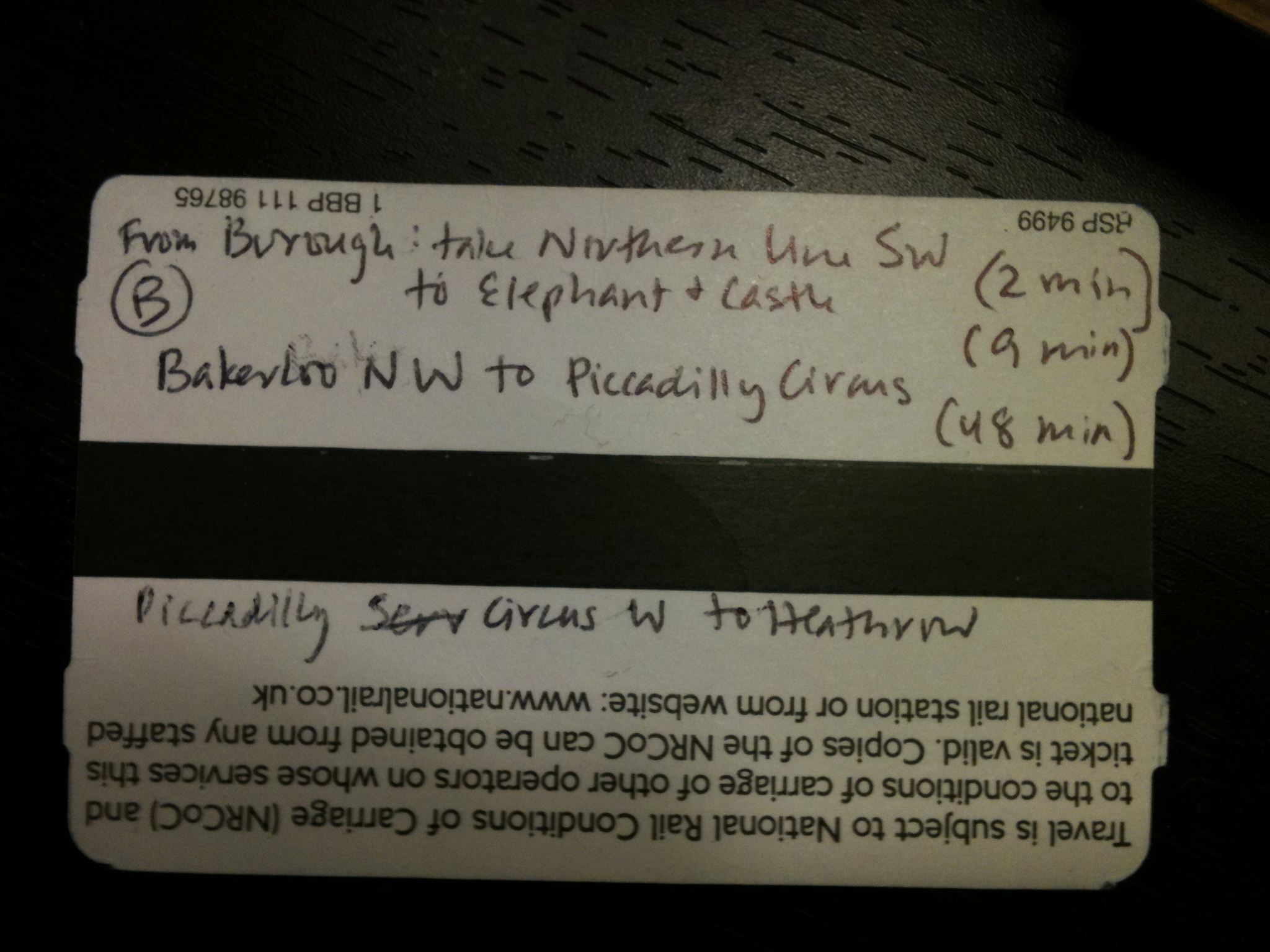

Then I labeled the two possible routes to the airport B:

and

C:

People with an innate understanding of public transit and/or the vaguest sense of direction will fail to understand the anxiety that motivates a lost soul to write distances in minutes. (My directions to A were written in feet: “walk on Long Lane for 127 ft., then turn right.”) Tube natives don’t need to note that a line is (NW) or (SW) because they carry maps in their head and—this is the most important part—they’ve learned not to take cardinal directions so literally. They aren’t flummoxed by that fatal crossroads where the Tube splits, perversely identifying a line that is clearly traveling in a southwesterly direction as either Southbound or Westbound. (Or, worse, when the same southbound line splits into TWO southbound lines, colored identically, but with different destinations—those are the moments that really confirmed me as a map-atheist.)

Anyway, I left my conditioner at Will’s and made it to the London Marylebone station, where I decided to scrap route B and just buy a train ticket to Heathrow because I couldn’t take the combined strain of another set of tube stairs and another set of tube transfers.

In the last three weeks, Irene and I had brought train tickets from the machines on no fewer than five separate occasions. I took one look at the machines and went straight to the information window, where I sweatily consulted one of the station attendants.

“You’re from San Francisco,” he said.

“How did you know that?” I asked, genuinely amazed. Was it my accent? My hair? My free-spirited West Coast je ne sais quoi?

“You said you wanted to take the BART to Heathrow,” he said, handing me my train ticket.

The next day I woke up at 6:15 a.m. with a sense of indefatigable will. I would make it to the airport! Only two sets of stairs on the BART! I had my train ticket in hand!

I navigated the underground with ease; at both transfer points, just as I was halfway up the stairs, rather proud of my progress, two different people took pity on me and carried my suitcase the rest of the way up. This proves it: anyone who says Londoners are cold and unhelpful is just insufficiently pathetic.

The next theater of battle was Paddington Station. Everywhere you look there are signs for the Heathrow Express. HEATHROW EXPRESS! say the arrows at all the coffee places. Heathrow Express: one every minute! says the screen directing you to various platforms.

I had rather cannily (I thought) avoided paying fifteen pounds for the Heathrow Express in favor of taking the Heathrow Connect, which takes fifteen minutes longer but is seven pounds cheaper.

The trouble was, I couldn’t find a single reference to the Heathrow Connect on any of the computer screens.

Once again I consulted a station agent, who pointed to the very last platform, all the way on the other end of the station, behind some construction work. “Platform 12,” he said. “It’s on the screen.”

Platform 12 had none of the accoutrements of the other platforms: no sign displaying when the next train would come, no people waiting for the same train. Just a number, 12, next to a deserted bit of track. I gnawed nervously at an apricot Danish.

Eventually two women joined me, and we watched from our dim distant corner as eighteen Heathrow Expresses came and went. One of the women, an American, had done this before, so the German woman and I followed her like baby ducklings to where she was waiting. It was only fifteen feet away from where we’d been standing, but it seemed infinitely more official.

The train finally pulled into the station. A tidal wave of people poured out, flooding the hitherto abandoned platform. My earlier smugness came back: clearly these were the natives, the travelers who knew what’s what and refused to pay a silly extra seven pounds for the privilege of fifteen minutes.

The German woman, the American and I got on the train and settled comfortably into our near-empty carriage. I put my train ticket on my right thigh so that it would be ready to hand the ticket inspector with a minimum of fuss. I felt composed, capable. I had even had the foresight to buy a cup of tea.

When the train inspector came, I watched the others digging in their bags for their tickets. When he got to me I calmly handed him my ticket.

“What is this?” he said.

I looked up.

“What?”

“This,” he said, handing it back to me.

This is what I saw:

“Oh!” I said, and started to rummage desperately through my bag. The German and the American stared. The inspector stared.

I pulled out one train ticket after another. Plans A and C were in evidence, but there was no sign of the train ticket to Heathrow.

“There is a fine for not having a ticket,” the agent said.

“I have it! I bought it yesterday!” I rummaged frantically. I was trying hard not to remember that I had managed, in the last month, to disappear both my passport and my Oyster card.

He sighed. “I’ll come back.”

I found it, and arrived home, triumphant, and went, jet-lagged but happy to the grocery store, for the express purpose of buying more conditioner so I could wash the airplane out of my hair. This was worth it, I thought—I should always leave half-used toiletries behind. It’s silly to carry something so replaceable with you. Yes, it’s wasteful, but maybe this is what responsible travelers do: acknowledge the fact that waste is intrinsic to traveling, and prepare accordingly.

I realized, in the shower, after shampooing, that I’d forgotten to bring in my new conditioner with me. I called for my partner to bring me my conditioner.

“Where is it?” he asked.

“Right there,” I said, pointing to it on the bathroom sink. “Just hand it to me.”

“That’s not conditioner,” he said.

“Oh, yes it is,” I said, condescendingly. “The white bottle. The same conditioner I always get. I left the one I had in England.”

He handed it to me, the nice new bottle I had paid a little too much for.

I stared at the words “ultra-whipped egg white” and “shampoo,” unable to reconcile them. “But it’s exactly like my bottle of conditioner!” I said. “They probably make both,” my partner observed, sagely.

My hair was an intractable tangle in need of something to help me pull a comb through it. I thought of eggs, and of that girl from the Noxzema commercial who said in an early 90s issue of YM that she used some sort of condiment in her hair. “Bring me a knife!” I said.

He did. And that’s how, despite the best-laid plans, however many bottles you abandon and train tickets you deface to better navigate an unforgiving world, you will—if fate decrees it—end up unconditioned in the shower, with liters of shampoo and a greasy butterknife, slathering mayonnaise on your head.